January 6th marks the 140th Anniversary of Carl Sandburg’s birth. A true 20th Century Renaissance Man, among Sandburg’s accomplishments is bringing Lincoln to life for many early 20th Century Americans in The Prairie Years and The War Years.

Born in 1878, by the time Carl began school, he changed his name to the “more American” Charles. One of seven children, “Charles” left school in 8th grade to drives a milk wagon. In 1896, he procures a three-day pass to Chicago courtesy of his father’s job in the Quincy, IL railyard. He spends all three days there. By 1878, he is gone for Galesburg.

Born in 1878, by the time Carl began school, he changed his name to the “more American” Charles. One of seven children, “Charles” left school in 8th grade to drives a milk wagon. In 1896, he procures a three-day pass to Chicago courtesy of his father’s job in the Quincy, IL railyard. He spends all three days there. By 1878, he is gone for Galesburg.

He spent the next years drifting; riding the rails. He is the quintessential hobo of the day. He must have made a rookie mistake in 1902. Arrested in Pennsylvania, he sat in jail for a week because he couldn’t pay his fare. He served for 8 months in the Spanish American War, tried college home in Illinois, was booted out of West Point-ironically because he flunked is first grammar exam, then worked a variety of jobs, intermittently.

Somewhere along the way he learned to play guitar. He began collecting the local folk songs he heard and he interviewed people. He wrote songs about their lives, too. Music would be a lifelong love for him. A musician would be a wonderful diversion around a hobo camp; a rallying siren on the campaign trail, too. He wrote poetry as the landscape flew past. The musical rhythm of the rails and his wanderlust were at the beginning of their lifelong friendship.

He re-enrolled at Lombard College. Philip Green Wright, an economics professor who would go on to teach at Harvard, strongly supports his efforts. Additionally, Wright moonlighted as a poet, too as well as a printing hobbyist. Sandburg begins to write in earnest. He leaves college without a degree but with a new a sense of what he wants to do.

It was a time in our history when people gathered to hear lectures and talks by professional orators. Chicago’s Bug House Square, across from the Newberry Library, served this purpose. Sandburg joined a travelling lecture circuit. He sang songs, gave talks, and sold little pamphlets printed by Wright. These reprints of his lectures included a few pages of his own poetry.

By 1904, professor Wright publishes Sandburg’s first collection of only poetry, In Reckless Ecstasy. The same year, his poetry and prose volume Incidentals went on the letterpress. Others followed, but few sales did.

In 1907, Sandburg is hired to speak in Racine, WI. The Social-Democratic Party leader is so impressed that he gives Sandburg a party organizer job. For the next five years, Sandburg campaigned for the party; working especially hard to reform child labor laws. Carl is again riding the rails, but this time as a paying customer! He crisscrosses the state campaigning for Socialist causes.

Carl Sandburg and Lillian Steichen arrived in Milwaukee on the same day that winter. Lillian was saying good bye to her friends at party headquarters. After, she would go home to her teaching job in Princeton, IL. Later that year, after countless letters-sometimes even two a day-Lillian and Charles were married in Milwaukee.

Lillian Steichen’s brother was Edward Steichen, the important American photographer. Steichen’s work influenced American citizen involvement in both world wars. He also is responsible for elevating fashion photography to an art form; as well as being a painter and a curator. From Vogue to Victory, he was truly a photographer’s photographer. It was Edward who was the go-between when Edward and Lillian’s parents strongly objected to a mere political organizer and poet with an arrest record marrying their University of Chicago-educated, Phi Betta Kappa daughter. Carl, Lillian and Edward had a lifelong bond forged in respect and love.

The Sandburgs lived in many places in Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Wauwatosa, and Appleton. He continued to self-publish poetry and prose, with little success. Lillian bred chickens and expanded her skills as an amateur geneticist and farmer.

By 1910 Carl’s dedication helps fuel a Socialist victory. Their candidate, Emil Seidel, won the Milwaukee mayoral race. Sandburg is appointed Secretary to the Mayor. In his spare time, he began experimenting with rugged, unorthodox free verse. He is inspired by the lives of the working people and the places he sees daily. That summer the Sandburg’s daughter, Margaret is born.

By 1912, frustrated with the plodding pace of reform, Sandburg takes writing jobs in Chicago. He will be working for two Socialist publications. Both published his poetry, too. The family moved to Ravenswood; a neighborhood near the north branch of the Chicago river. Their little home stands today and is only a few blocks from where Mayor Rahm Emmanuel lives today.

That spring, Chicago hosted the International Exposition of Modern Art—the infamous Armory Show. Even though it had been severely toned down from the New York version, the Chicago debut left art lovers shocked and disgusted. Works like DuChamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase caused the scandal to reach the governor’s office. The White Slavery Commission investigated.

But, soon the breezes of change would be blowing through the entire cultural landscape of Chicago and beyond.

1913 would prove a turning point in Sandburg’s life in many ways. He was hired by The Day Book,and was free to write what he wanted, eventually publishing over 100 columns. He picked up a freelance job, too. It meant he could support his family and write poetry at night. That was the writing that gave him the deepest satisfaction. By the summer of 1913, Sandburg has written the poem he titled Chicago.

In the fall, Sandburg’s second child, Madeline, dies during her birth; Carl is fired from The Day Book. When Lillian submits Chicago toThe American Magazine, the poem is rejected.

That winter, the couple chose nine poems to submit to Poetry: A Magazine of Verse.

Dedicated to only poetry and edited by Chicago Art and Culture denizen, Harriet Monroe, the magazine was funded by wealthy Chicagoans. Moore, who I like to think of as the grandmother of the poetry slam, accepted six of his poems for the March 1914 issue.

No mention of this era, dubbed “The Chicago Renaissance” would be complete without mentioning the Dill Pickle Club. Located in an alley, in Little Hell-the neighborhood we now call The Gold Coast-the club was a local hang-out frequented by the bohemians and free-thinkers that populated Chicago in those days. Carl became a long-time member of a scene that included Vachel Lindsay, Upton Sinclair and other Chicago literati and artists. I can imagine Sandburg and Lindsay sharing mad beats over strong whiskey late into the night.

No mention of this era, dubbed “The Chicago Renaissance” would be complete without mentioning the Dill Pickle Club. Located in an alley, in Little Hell-the neighborhood we now call The Gold Coast-the club was a local hang-out frequented by the bohemians and free-thinkers that populated Chicago in those days. Carl became a long-time member of a scene that included Vachel Lindsay, Upton Sinclair and other Chicago literati and artists. I can imagine Sandburg and Lindsay sharing mad beats over strong whiskey late into the night.

The Sandburgs anxiously awaited the March issue of Poetry.The reviews were not good. Readers objected to the brutality.The Dial,another Chicago literary magazine, found “no trace of beauty in the ragged lines.” It was like The Armory Show, except for Poetry!

But, as people started to understand the more modern tone that was sweeping through art and literature, opinions about Sandburg’s work changed. Later that year, Alfred Harcourt, from Henry Holt publishing, read the manuscript for Chicago Poems. He loved it and recommended it for publication.

Sandburg’s Chicago Poems saw its first printing in 1916. It is still in print today. In June of that year, Sandburg’s daughter, Janet was born.

Sandburg’s Chicago Poems saw its first printing in 1916. It is still in print today. In June of that year, Sandburg’s daughter, Janet was born.

With his chops as a writer firmly established, Sandburg started working as a reporter for the Chicago Daily News late in 1917. He would stay for thirteen years. The only time he left Chicago during his tenure was in 1918. His daughter, Helga was born while he was away covering World War I.

In 1919, he shared the National Poetry Society of America Prize (the forerunner of the official Pulitzer Prize) for Cornhuskers.He adds the title Film Critic to his job at the Chicago Daily News.

In the years from the publication of Chicago Poems to the day he left the Chicago Daily News, he published a dozen other works; including poetry, prose, children’s books, folk music anthologies and his biography of Lincoln’s early life, The Prairie Years.

The success of The Prairie Years allowed Sandburg to write full time. By the late 20s the family had moved to Michigan. Lillian wanted a small farm. Her skills in animal husbandry created two of her chicken breeds, both are prized even today. It was Carl’s idea that she raise dairy goats and Michigan was a much better place than the Chicago area for that. Carl would commute to Chicago on the train a few days a week.

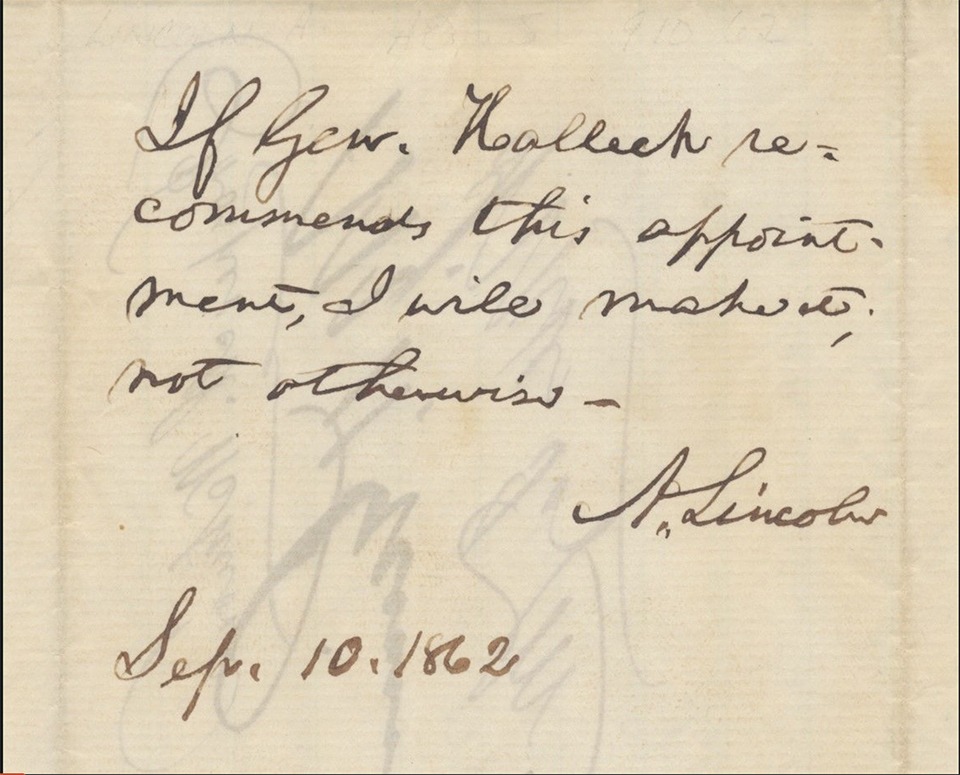

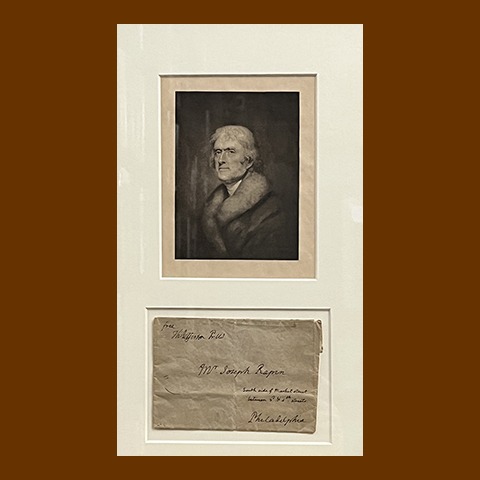

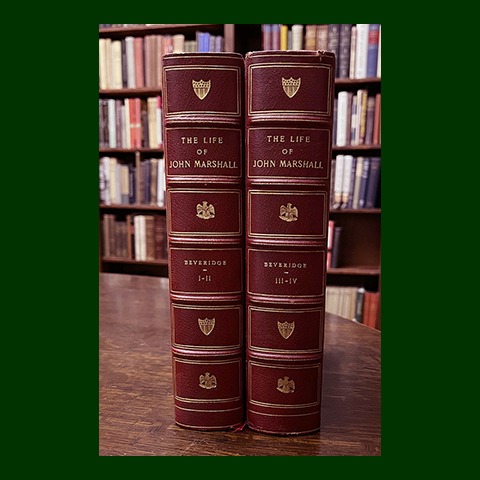

Sandburg’s obsession with Lincoln–there was a fireproof vault in his home where he kept his Lincoln papers–drove him to finish Lincoln’s life story. The War Years, dominated his creative life until its completion in 1939. It was during this time he began to frequent Abraham Lincoln Book Shop. Carl was part of the original circle of Civil War and Lincoln enthusiasts that included authors Bruce Catton, Otto Eisenschiml, E. B. ‘Pete’ Long, Stanley Horn, Lloyd Lewis, and T. Harry Williams, Illinois Governor Otto Kerner and William O. Douglas, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The logo inside The Prairie Years inspired our logo, too. Sandburg received his second Pulitzer Prize for the four-volume work in 1940.

Sandburg’s obsession with Lincoln–there was a fireproof vault in his home where he kept his Lincoln papers–drove him to finish Lincoln’s life story. The War Years, dominated his creative life until its completion in 1939. It was during this time he began to frequent Abraham Lincoln Book Shop. Carl was part of the original circle of Civil War and Lincoln enthusiasts that included authors Bruce Catton, Otto Eisenschiml, E. B. ‘Pete’ Long, Stanley Horn, Lloyd Lewis, and T. Harry Williams, Illinois Governor Otto Kerner and William O. Douglas, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The logo inside The Prairie Years inspired our logo, too. Sandburg received his second Pulitzer Prize for the four-volume work in 1940.

The next three decades brought not only The War Years, but over 40 other titles ranging from biography, children’s books, musical anthology, poetry. Trying a new genre, his only novel, Remembrance Rock joined the list. Sandburg also garnered his first film credit during World War II. He wrote the script for Bomber, a 1941 film documentary detailing the manufacturing of warplanes.

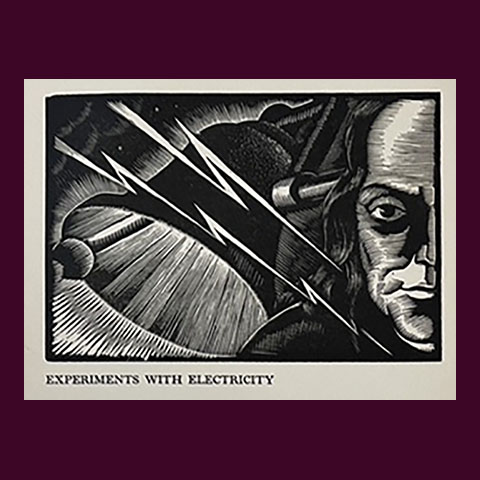

Sandburg was thrilled to work on projects with Edward Steichen during this era, too, Sandburg wrote the text for Steichen: The Photographer and collaborated on Road to Victory, Steichen’s World War II photographic exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. Sandburg’s authored the interpretive panels and the companion book to the exhibit. Hastily assembled in the months following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, it showed people how they could aid the war effort.

Sandburg was thrilled to work on projects with Edward Steichen during this era, too, Sandburg wrote the text for Steichen: The Photographer and collaborated on Road to Victory, Steichen’s World War II photographic exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. Sandburg’s authored the interpretive panels and the companion book to the exhibit. Hastily assembled in the months following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, it showed people how they could aid the war effort.

By 1945, the Sandburg family moved to their beloved home, Connemara, in Flat Rock, NC. It was primarily at Lillian’s desire, for the benefit of the goat farm. It had greener pastures and a longer growing season. Eventually she would found two goat breeds. Both thrive today at Connermara and are prized for their milk. Carl continued to publish poetry, prose, children’s books, and a couple of autobiographies. An elder bard of the era, his popularity only increased. His Complete Poems earned him his third Pulitzer Prize in 1951.

Edward Steichen honored his brother-in-law’s literary accomplishments In 1953. Steichen organized a photographic exhibit featuring the works of talented your imagists. The exhibit was titled Always the Young Strangers, after Sandburg’s then just-released book.

After World War II, Steichen served as the Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art. During his tenure, Carl wrote the text for the exhibition catalog for Steichen’s acclaimed Family of Man exhibit. Opening in 1955, this vast collection includes over 500 photos depicting life, love and death in 68 countries. The exhibit has a permanent home in northern Luxembourg.

In 1958, Sandburg appeared at the parole hearing of Nathan Leopold. Leopold’s attorney, Elmer Gertz, had defended Henry Miller and Jack Ruby. Ever the strong advocate of reform, we will never know what Sandburg said because the stenographer’s machine jammed during his testimony. However, Leopold was granted parole and shortly after left the country forever.

The 1960’s saw the stage production of The World of Carl Sandburg, he even had a cameo at the end of the show. Also during the era, he campaigned tirelessly for John F. Kennedy. Mid-decade the last book in his lifetime, Honey and Salt was released, he also received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Johnson.

The 1960’s saw the stage production of The World of Carl Sandburg, he even had a cameo at the end of the show. Also during the era, he campaigned tirelessly for John F. Kennedy. Mid-decade the last book in his lifetime, Honey and Salt was released, he also received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Johnson.

The Civil War Centennial provided ample speaking and singing invitations, too. Collecting the music he heard as he travelled gave him fodder for his three enormously popular musical anthologies. In the process, he saved a great deal of regional music from being lost forever.

Carl Sandburg died in 1967 at his beloved Connermara. His ashes are entombed at the home in Galesburg, under a boulder called Remembrance Rock. Lillian is there, too. The brick path to the rock is lined with flagstones that bear quotes from popular Sandburg poems.

Sandburg’s daughters carried on their parent’s legacies in both writing and animal husbandry. Embraced by his hometown, Galesburg hosts Sandburg Days every spring. Connermara was the first National Park Site dedicated to a poet. It even has goats!

Sandburg himself would probably be most proud of Carl Sandburg College in Galesburg. Sandburg and Philip Green Wright envisioned such a college. They saw “a college, where people of all ages could learn everything from literature and art to metalworking and beekeeping.” It held its first classes in the fall of 1967; a few months after Sandburg’s death. It still has a similar mission today.

For me, he is the true 20th Century Renaissance man; a flaneur of culture. He wanders among it, collecting the things he loves, making them his own and then sharing them so we can learn to love them, too.

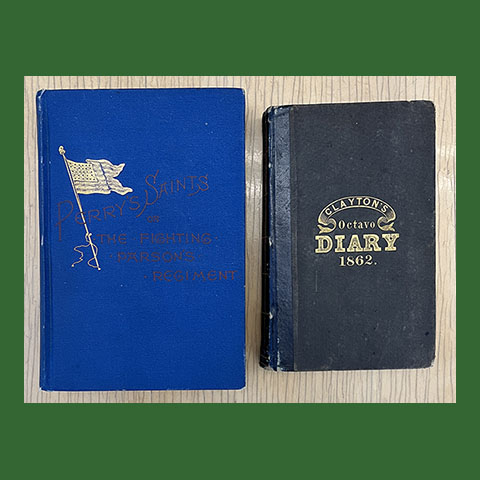

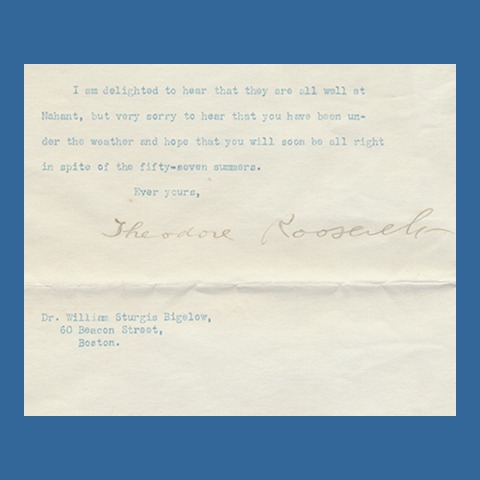

Abraham Lincoln Book Shop has many wonderful Carl Sandburg items. If you come to the shop and sit on all the chairs at our round table you will surely sit in a chair that Carl occupied during one of his many visits to the book shop.

Take a look at our Carl Sandburg offerings today!

M. Sylvia Castle